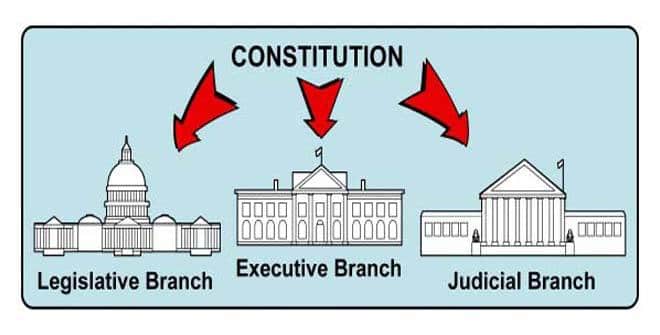

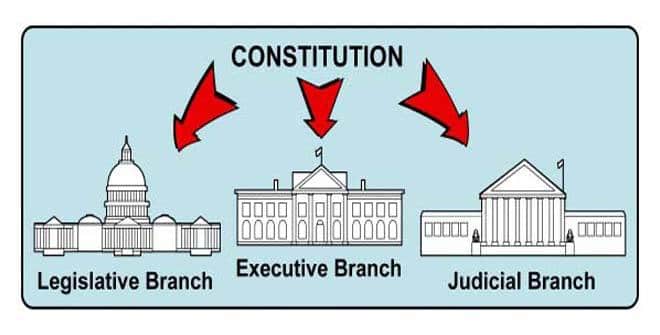

Separation of powers

The principle of separation of powers is implied in the

division of powers in the Constitution

among the three (3) government branches: the executive, the legislative, and the

judiciary.[1] “The principle presupposes

mutual respect by and between the

executive, legislative[,] and judicial departments of the government and calls

for them to be left alone to discharge their duties as they see fit.”[2] “The

executive power [is] vested in the President of the Philippines.”[3] The

President has the duty to ensure the faithful execution of the laws.[4] The

President has the power of control over “all the executive departments, bureaus,

and offices”[5] including, among others, the Department of Energy, the

Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the Department of Science and

Technology, and the Department of Public Works and Highways.

“The

executive power [is] vested in the President of the Philippines.”[3] The

President has the duty to ensure the faithful execution of the laws.[4] The

President has the power of control over “all the executive departments, bureaus,

and offices”[5] including, among others, the Department of Energy, the

Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the Department of Science and

Technology, and the Department of Public Works and Highways.

The Constitution vests legislative power in the Congress.[6] The Congress enacts laws.

Meanwhile, judicial power is vested in the Supreme Court and other courts.[7] Judicial power refers to the “duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights [that] are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether . . . there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government.”[8] Essentially, the judiciary’s power is to interpret the law with finality.

The powers specifically vested by the Constitution in each branch may not be legally taken nor exercised by the other branches. Each government branch has exclusive authority to exercise the powers granted to it. Any encroachment of powers is ultra vires; it is void.

Thus, the legislative branch is not authorized to execute laws or participate in the execution of these laws. It also cannot make interpretations of the law with finality.[9]

The executive department cannot make legislative enactments. Like the legislative department, it cannot make final interpretations of the law.[10]

The judiciary has no power to execute laws[11] or take an active part in the execution of laws. It has no supervisory power over executive agencies.[12] The judiciary has no power to create laws[13] or revise legislative actions.[14] Even the Supreme Court cannot assume superiority on matters that require technical expertise. It may only act as a court, settle actual cases and controversies, and, in proper cases and when challenged, declare acts as void for being unconstitutional.

“The

executive power [is] vested in the President of the Philippines.”[3] The

President has the duty to ensure the faithful execution of the laws.[4] The

President has the power of control over “all the executive departments, bureaus,

and offices”[5] including, among others, the Department of Energy, the

Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the Department of Science and

Technology, and the Department of Public Works and Highways.

“The

executive power [is] vested in the President of the Philippines.”[3] The

President has the duty to ensure the faithful execution of the laws.[4] The

President has the power of control over “all the executive departments, bureaus,

and offices”[5] including, among others, the Department of Energy, the

Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the Department of Science and

Technology, and the Department of Public Works and Highways.The Constitution vests legislative power in the Congress.[6] The Congress enacts laws.

Meanwhile, judicial power is vested in the Supreme Court and other courts.[7] Judicial power refers to the “duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights [that] are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether . . . there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government.”[8] Essentially, the judiciary’s power is to interpret the law with finality.

The powers specifically vested by the Constitution in each branch may not be legally taken nor exercised by the other branches. Each government branch has exclusive authority to exercise the powers granted to it. Any encroachment of powers is ultra vires; it is void.

Thus, the legislative branch is not authorized to execute laws or participate in the execution of these laws. It also cannot make interpretations of the law with finality.[9]

The executive department cannot make legislative enactments. Like the legislative department, it cannot make final interpretations of the law.[10]

The judiciary has no power to execute laws[11] or take an active part in the execution of laws. It has no supervisory power over executive agencies.[12] The judiciary has no power to create laws[13] or revise legislative actions.[14] Even the Supreme Court cannot assume superiority on matters that require technical expertise. It may only act as a court, settle actual cases and controversies, and, in proper cases and when challenged, declare acts as void for being unconstitutional.

[1] Angara v. Electoral Commission, 63 Phil. 139, 156 (1936) [Per J.

Laurel, En Banc].

[2] Anak Mindanao Party-List Group v. Executive

Secretary Ermita, 558 Phil. 338, 353 (2007) [Per J. Carpio Morales, En Banc],

citing Atitiw v. Zamora, 508 Phil. 321, 342 (2005) [Per J. Tinga, En Banc].

[3]

CONST., art. VII, sec. 1.

[4] CONST., art. VII, sec. 17.

[5] CONST., art. VII, sec. 17.

[6] CONST., art. VI, sec. 1.

[7] CONST.,

art. VIII, sec. 1.

[8] CONST., art. VIII, sec. 1.

[9] See

Belgica v. Executive Secretary Ochoa Jr., G.R. No. 208566, November 19, 2013,

710 SCRA 1, 107 [Per J. Perlas-Bernabe, En Banc], citing Government of the

Philippine Islands v. Springer, 277 US 189, 203 (1928).

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] CONST., art. VII, sec. 17.

[13] See

Belgica v. Executive Secretary Ochoa Jr., G.R. No. 208566, November 19, 2013,

710 SCRA 1, 107 [Per J. Perlas-Bernabe, En Banc], citing Government of the

Philippine Islands v. Springer, 277 US 189, 203 (1928).

[14] See

Vera v. Avelino, 77 Phil. 192, 201 (1946) [Per J. Bengzon, En Banc], citing

Alejandrino v. Quezon, 46 Phil. 83, 93 (1924) [Per J. Malcolm, En Banc].